The task: document the ideal Summer weekend (aboard a HB.130, obviously.)

...and the third instalment comes from Rosie Holdsworth.

Goshawks are one of the UK’s rarest birds of prey. They’re also one of the most difficult to spot.

Last September, part way through a big old ride from the Lakes to Edinburgh, in the deepest darkest depths of Kielder Forest induced despair; I saw a Goshawk! A massive female sat on a branch on the forest edge long enough for my gravel-addled brain to catch up with the information my eyes were sending it, but not quite long enough for me to come to a safe and controlled stop. The resulting crash into a ditch and associated gravel-rash meant I only caught a glimpse of her as she powered away across the glade and over the trees out of sight.

Since that chance encounter – Goshawks have got under my skin. They’re special birds, known in different cultures as the ghosts of the woods; in ancient celtic traditions, to utter their name is to bring death and destitution on your household. They’ve long been prized as falconry birds and their Latin name Accipiter gentilis reflects the tradition that only nobles were considered worthy of flying them. Few other raptors have the same amount of myth and folklore associated with them. Goshawks’ more recent history has been less distinguished: they were persecuted by traditional gamekeepers and egg collectors for decades, until eventually they became extinct in the UK by the end of the 19th Century. The UK’s wild population today is the result of escapes and accidental releases of falconry birds since the ‘60s and they’ve benefitted from increase in forest cover and protective legislation ever since. To catch a glimpse of one is to be instantly hooked – I had to get back for more!

Goshawks frequent forest edges and often hunt around commercial forestry plantations and moorland edges, which also happens to be where some of the best bicycle action is. I’d been itching to get back to the English-Scottish border country, with a proper bike this time, to enjoy some beautiful riding and see if I could capture more than a fleeting glimpse of this elusive and impressive hawk. When the call came from Hope to devise a summer adventure, I only ever had one mission in mind. I hatched a plan to get back up to Northumberland with my old pal Pete, who’s fairly handy on a bike and with a camera, as well as being even more excitable than me when it comes to tracking down and spotting birds of prey.

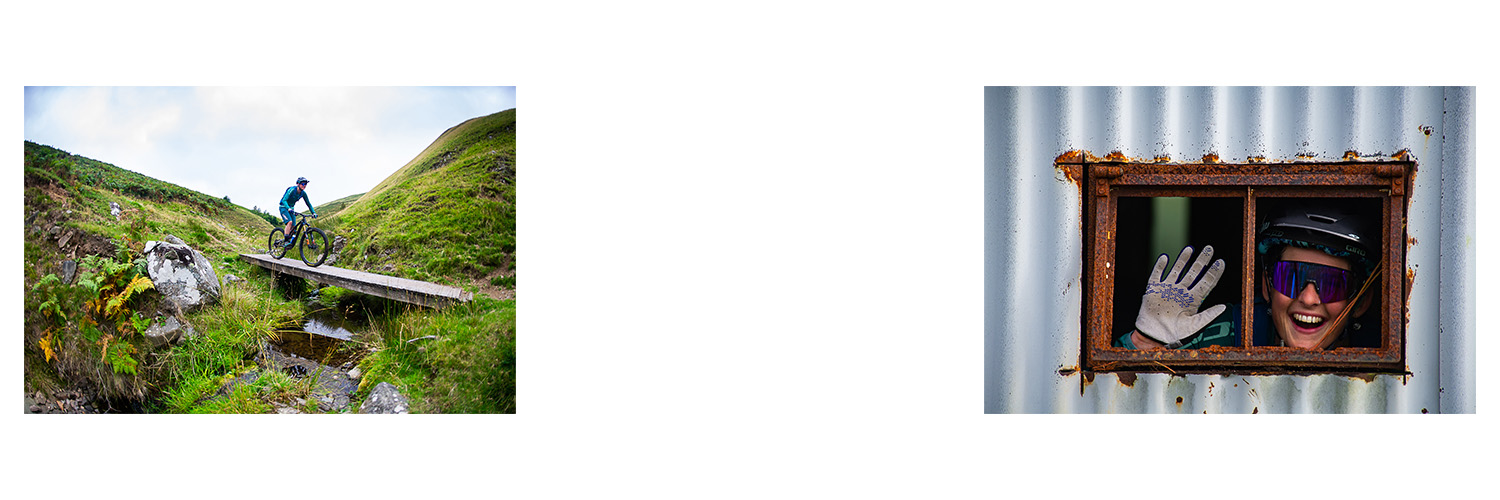

This felt like a perfect trip for the HB130: The routes planned were MTB classics, with some sturdy climbs and fast, rough descents. But I’d never ridden in this corner of the world before, so was unsure exactly what to expect. I knew the HB130 would climb all day, but also that it would be more than capable of handing whatever rocky descent or rooty chute lay round the corner in much more composed fashion than I might.

Coquetdale in the Northumberland National Park ticks lots of boxes for birds of prey in general – and Goshawks in particular. Expansive moorlands interspersed with dense commercial forestry blocks and scatterings of mixed woodlands hit all the criteria for spooky, murderous hawks. Add to that the plentiful supply of woodpigeons, ducks, meadow pipets and grouse, as well as a recent hot-tip from a birdy friend, and it was top of the list of locations to try. So we headed out on a classic ride; following Clennell Street (an ancient drove rode) up and out of the valley and onto the rolling Northumbrian hilltops.

Around every turn in the trail more birds appeared, usually the ubiquitous meadow pipits; staple of every discerning raptor. Pete and I frequently ditched our bikes in excitement as we glimpsed fast flying grey birds emerge from forestry blocks, only to realise it was another bloody pigeon and clamber back on the bikes.

Wildlife in general certainly wasn’t in short supply and Pete gracefully tolerated my frequent interludes to inspect fungi, rescue stricken bees, prod caterpillars and collect feathers. Summer’s tail end is a relatively quiet time for wildlife, as everything seems to take a deep breath before the challenge of piling on fat in autumn to get through winter. Nature was out to put on a show despite this and we encountered numerous buzzards, kestrels, wrens, finches and geese as we descended… but still no Goshawk!

Meandering alongside a babbling brook, we hopped off the bikes to open a gate and as I wheeled through I glimpsed a hidden treasure in the grass… Closer inspection confirmed what I’d barely dared to hope: A Goshawk feather!

Buoyed by the confirmation that Goshawks were definitely calling this corner of the country home, we continued along the beautiful valley with our eyes on the skies.

Alas, we returned to the vans without a sighting. Time to top up the pasta levels and find a camping spot before lights out. Camping spot located and bellies full of Northumberland’s finest Italian cuisine, we had time to kick back with a brew and watch the stars come out whilst the tawny owls serenaded us with their screeches.

We were up early the next day, filled with renewed optimism that the ghost of the woods might prove less elusive. A hearty cooked breakfast in Wooler only added to our enthusiasm and we headed for the beautiful College Valley at the foot of the Cheviot hills convinced today would prove more fruitful.

Seemingly in line with most valleys in Northumberland, the College Valley boasts an enviable array of historic sites and stories. The hills either side of the valley are littered with hillforts, hut circles and air crash wrecks and associated tales of tragedy and daring do – including that of Sheila the Collie dog who was the first civilian animal to receive the Dickin Medal for rescuing 4 airmen from their wrecked B17 Flying Fortress in 1944. With mixed moorland, broadleaf and coniferous woodland habitats; the College Valley is prime habitat for Goshawks. Add to that mix the varied wildlife and the WWII history and it’s also perfect habitat for a nature nerd and a plane geek – me and Pete were in our element!

The valley was full of birdlife; much like the day before, we were spotting buzzards and kestrels round every corner. A commercial conifer block was too tempting to miss and we headed in for a closer inspection. We could hear buzzards calling above and could see them making low passes just above the trees. Were they just making a racket, or had they spotted an elusive Goshawk?

The dense trees made it almost impossible to see what the buzzards were shouting about – oh for a bird’s eye view! We hung round long enough to satisfy ourselves that it was just buzzard horseplay and continued through the forest. My eye was caught once again by feathers, this time a selection of different feathers caught up in the branches of a larch. Something large, airborne and bird-eating had almost certainly nested here earlier in the year. More Goshawk evidence, but still no Goshawk!

Feeling slightly defeated, we meandered through the forest, willing every gust of wind and rustle of foliage to produce our fearsome raptor quarry. We consoled ourselves with lunch in a sunny spot and a conversation with one of the last butterflies of the year.

Rolling reluctantly back to the cars, we admitted defeat; the ghost of the woods had succeeded in eluding us. Like any good crime novel, the tantalising clues left by our target only served to strengthen my determination to head out again and seek them out. I’m determined I’ll be back up north early next year to see if I can catch Goshawks in their spectacular springtime skydance displays. For the time being though, that solitary feather will have to suffice.

Words: Rosie Holdsworth

Photos: Pete Scullion